In the course of examining the grievances of mid-19th century Evangelicals in the Protestant Episcopal Church, especially their concerns with the Prayer Book, I ran across Wesley’s possible influence on the 1785/89 Liturgy. Whatever proof remains of this influence may very well boil down to a correct rendition of dates. This is likely a work in progress.

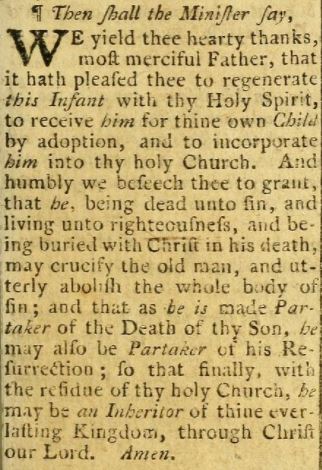

Mid-19th century Evangelical Episcopalians were placed on the defense by the rising tide of Anglo-Catholicism, so the Liturgy became one of several sites of battle over Church doctrine. Of substantial concern was the language of the Baptismal Office which dubiously declared ‘Seeing how this child be regenerate’. Evangelicals quickly became anxious, wanting an alternative phrase (and for those parts of the Office the term ‘regenerate’ elsewhere cropped up), with a significant number begging for legal relief at the 1868 and 1871 General Conventions. Naturally, part of this Relief involved the modification of the Baptismal language found in the 1789 Prayer Book (BCP) which said:

Leaders of Evangelical protest, like the Rt. Rev. George D. Cummins, generally felt improvement could be had by returning or basing reform upon the ‘first’ version of the American BCP, adopted by the limited Convention of 1785 (Connecticut abstained). This was a prayer book especially diligent of comprehension efforts dating back to 1689 and 1661. The 1785 Preface, written by the Rev. Dr. William Smith, gave much praise to these earlier attempts, and Victorian Evangelicals were relatively convinced the 1785 held a relevant basis for unity with other American Protestants. Not all churchmen, of course, agreed, and there were many moderate Evangelicals like the Rt. Rev. Alfred Lee, though not differing with Cummins on principle, felt the 1789 BCP was adequate to the same end, mostly, due to its closeness to the 1785 proposed Book. Regardless, here was Dr. Smith’s sentiment behind the American Liturgy:

The foremost concern of Victorian Evangelicals with the baptismal liturgy for Infants was it entertained certain ‘Romanist views’ with terms like ‘regenerate’, and that such be either reworded or omitted. Following the example of the 1785 Book, embattled Evangelicals would have omitted the Bidding Prayer yet reworded the Thanksgiving after Baptism. Among Evangelicals who departed the Episcopal church, opinion changed with time, but early-on the low-church party favored the alterations of 1785. A modification from the language of 1785 Book had the advantage of being an ‘episcopal’ one– or, at least, an amendment that easily stood within the pale of the American church’s history. So, it read:

Initially, I believed this wording was original to the American church. Though the arguments for non-conformity were reviewed, neither the 1689 nor the 1661 Committees bothered to go so far with alterations as to adopt alternative language for ‘regeneration’. Therefore, these Committees, lauded by Dr. Smith, were not the sources of the amended terminology. Either the language above was original to Dr. Smith’s pen, or it derived from another source outside the Episcopal church, perhaps moderate Dissent?

However, after cross-referencing Mr. John Wesley’s Sunday Services– both the American and English versions– the identical prayer was happily discovered. The Sunday Service for the Methodists in North America (slightly older than the English version) can be dated by the letter affixed to the beginning of the book, written from England by Wesley and sent to his Assistants in the colonies, Dr. Coke and Mr. Asbury. It is dated Sept. 10, 1784. Compare this to the date of Dr. Smith’s commission for the compiling of a proposed Book at the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church, which is Sept. 27th 1785. Between the two, there is about a year’s difference, so it seems a reasonable time for diffusion of Wesley’s Service across the Atlantic.

As far as I know, this (maybe) trivial point about the 1785 Baptismal service has received little noticed. What it testifies, however, is the likely impact church Methodists had on Protestant Episcopalians (and this influence is likely wider than the Baptismal service). In other words, methodists like Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey whose loyalty to establishment compelled them to join the Protestant Episcopal church in the USA. Quite possibly, it was from evangelical men like them by which Dr. Smith later drew the amendment. These ministers may very well have been using portions of Wesley’s form, or at least were knowledgeable about it, prior to the Philadelphia General Convention. Their departure from the Methodist Episcopal Church might have also been a particular factor in the abandonment of the Sunday Service among Methodists less endeared to their Father in the Gospel, Mr. Wesley. (For the disuse of Wesley’s Service see Karen B. W. Tucker, American Methodist Worship, p. 9).

Perhaps White’s drawing from Wesley’s service was an attempt to persuade Methodists into a more regular Episcopal body? Rhoden curiously suggests the influence of Methodism where she describes the making of the Protestant Episcopal Church,

“The General Convention of 1789 [as well as those, to an extent, preceding] had to reconcile three divergent views on church government: a middle and southern states’ church with English consecration and a representative clerical and lay convention; a New England church headed by a Scottish-consecrated bishop and governed by a clerical convention; and a Methodist Episcopal Church. A reunion with Methodists did not occur, but eventually northern and southern strains of Anglicanism quieted their hostilities. Regional tensions persisted, but did not prevent the formation of a national church” (see Nancy Rhoden, Revolutionary Anglicanism, p. 144)

An older source which Wesley likely drew might have been the Rev. Richard Baxter who, after the rounds of Savoy Conference, compiled non-conformist opinion into a liturgy for his Association colleagues at Kidderminster. I’ll see if I can garner any evidence for this theory, but I have an odd suspicion it may be true.

Until then, when comparing the amended versions pushed by Victorian Evangelicals in the early-Reformed Episcopal Church (the 1871 vs. 1874 RE BCPs), I’d have to say choosing the 1785 for the source of reform speaks with far more authority than making new prayers as the Reformed Episcopalians eventually did in 1874 (see Allen G. Guelzo, For the Union of Evangelical Christendom, p. 233-236). These later RE BCP revisions seem almost sympathetic of Baptists than Protestant Anglicanism or Methodism. Nonetheless, the 1785 Book language no only belongs as a vital part (if not the font) of American Episcopal liturgics, it has the added weight of the original Service book intended for the Methodists, recalling a special, albeit lost, connection between the two denominations, “Therefore, what God has joined together, let no one separate.”